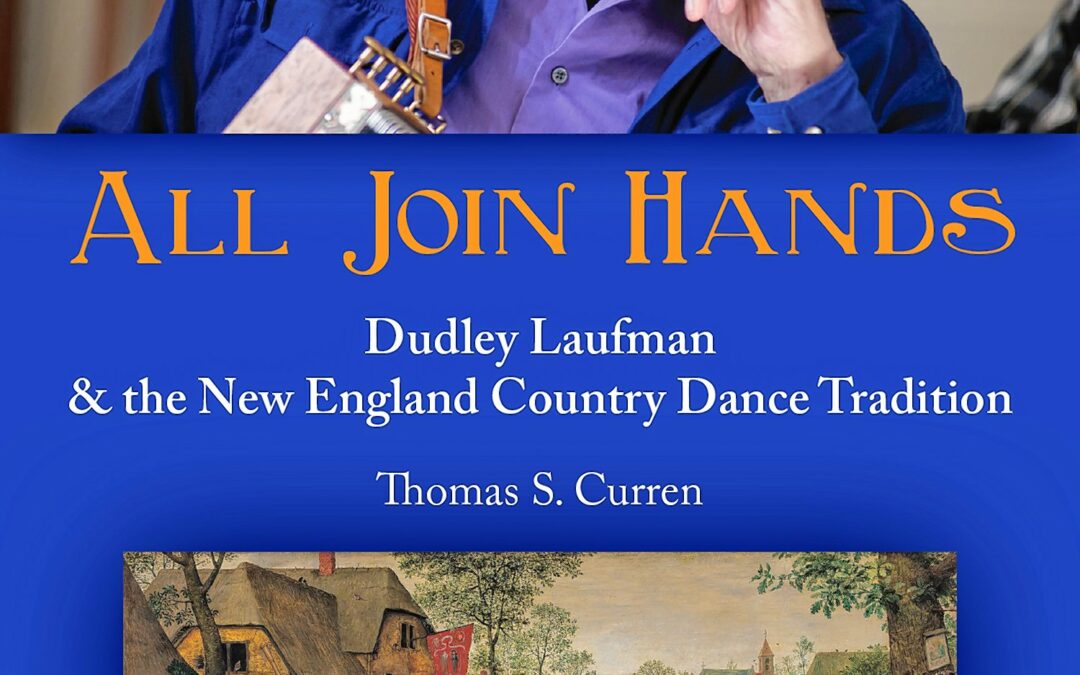

In New England, there has long been a deep affection for traditional dance and its corresponding music. Folk dance joins us together, lifting us out of inhibitions, anxieties, and our acculturated need to exert control. It requires our participation as individuals, yet we embrace it as an exercise in group dynamics. The Yankee instinct for community art has been the inspiration behind Dudley Laufman’s lifelong stewardship of country dance, which is the story at the heart of “All Join Hands,” a new book by Thomas Curren.

While in high school, Laufman — who grew up in Arlington, Mass., and now lives in Canterbury — apprenticed with fiddlers and callers throughout New England. Eventually, he squired the old country dance traditions through to their revival in the 1960s at the Newport Folk Festival, Club 47 (now Club Passim) in Harvard Square, and on Robert J. Lurtsema’s “Morning Pro Musica” radio broadcasts.

At the same time he narrates Laufman’s life and contribution, Curren — himself a folk musician — chronicles the roots of square dance (also known as contradance) in Europe and America, the folk revival of the 1960s and 1970s, and the commensurate back-to-the-land movement that has long sought to provide a sustainable alternative to the perils and pitfalls of consumer civilization. A book that chronicles the living tradition of New England country dance through the life’s work of one uniquely talented and determined man, “All Join Hands” shows us how, over the course of seven decades, one of the key cultural components of a region was revived and renewed.

Curren is a writer, farmer, conservationist, and historian. He has served as a town selectman, a town moderator, and a non-profit consultant, and volunteers for the Folk New England Archive at the University of Massachusetts. As project director with the Pew Charitable Trusts and as director of local conservation organizations, he has helped enable the conservation of nearly 900,000 acres in New England, New York, and Pennsylvania’s Amish country. An authority on New England culture and landscape, his previous books include “I Believe I’ll Go Back Home: Roots and Revival in New England Folk Music” as well as four histories of New Hampshire towns. Part of the group “The Good Old Plough,” he plays and sings traditional music — at times with Dudley Laufman and friends. He lives in rural New Hampshire.

Curren discusses his book, country dancing and his friendship with Laufman:

Most of us associate country dancing with Texas or the South. Are you saying it’s actually a New England thing?

Well, I’m not going to attempt to make the case that chili or Cajun shrimp soup are Yankee fare, but they are younger cousins to our baked beans and seafood chowder! In general, Anglo-European music traditions arrived first off the New England coast and then made their way westward and southward over time. For example, the old ballad song “Barbara Allen” was popular in England as early as the 1500s and came over here to Salem, Massachusetts in 1636 on a ship called the True Love. Imagine being in a position to say that your ancestors came over on the True Love!

After the Revolution, folk music headed with the settlers toward Appalachia, where the old Yankee jigs were converted into bluegrass hoedowns and the French “quadrilles” became square dances. The “Barbara Allen” song was collected in North Carolina in 1907 and by John Lomax in 1939 at Florida State Prison. When it was discovered by folkies in the 1960s (most likely on a Joan Baez album) the song was assumed to be a Southern piece … which it was, by then … but that was only the latest part of a long, long story. It’s a story that begins in New England, and one that deserves to be told.

What was true of songs was true of dances as well, and by the 20th century there was a lot more traditional dancing to be found in the rural South and West than in the settled and suburbanized East. I grew up associating square dancing with movies of couples dressed in cowboy hats and boots, jeans, and calico dresses whirling around dance halls in places like Tulsa and Bakersfield … much more associated with cattle round-ups than with Grange suppers!

What does a typical New England country dance look and sound like — can you describe it for us?

It takes place in a small hall, bordered by a modest stage on one end and a kitchen supplied with a collection of “covered dishes” and cider on the other. People of all ages tend to come early and visit with each other a bit, the musicians mingling with the dancers and the volunteers who are there to serve the food. At the advertised time, the caller will cue the musicians to “warm up” with a few pieces, and there’s a scramble as they tune their instruments and join in an opening number. Usually this is a well-recognized tune like “Red River Valley” or “Pop Goes the Weasel.” A few couples might take the floor and dance together, dressed in everything from flannel shirts or “peasant blouses” to jeans and western skirts.

Before each song, the caller announces the name of the dance, for example: “All right now, couples to the floor, please, we’re going to start off with good old ‘Petronella,’ ” and gives an aside to the musicians about key and tempo. The caller then sings out directions to the dancers: “Back around and you balance to your partner … now go round to your right and you balance once again … go around to the center and you bow … and you bring her right back home … and you cast off and you right-and-left back over … and you right-and-left right over and go home!”

This all might sound pretty daunting to first-timers, but the reality is that the whole thing can be reduced to holding hands and bouncing around in rhythm if that’s what works best for a couple. Generally, most of the dancers know the drill, and it is surprising how quickly the steps can be picked up … augmented with old 1950s record hop twirls or just faked, as the case may be. Every couple takes a turn leading while the rest of the set swings in place. The caller cues the close of every tune as it approaches, by calling the word “out,” which is the signal to the band to come to a close at the end of the next verse. Everybody applauds and gets ready for the next dance. At intermission folks are invited to fill a paper plate with some mac and cheese or tuna wiggle and chips … til the caller brings everyone together again on the floor, introduces the band members, and then presides over another hour or so of tunes, smiles, and swings. Everybody goes home happy.

You’re an historian, a musician, and a proud New Englander, so it’s not hard to see what attracted you to this topic once you knew about it. But how did you first find out about the New England country dance tradition?

Well, as your first question might have anticipated, I first saw square dances in cowboy movies on WBZ TV! I think in person it was probably at a Grange event in Parsonsfield, Maine, where my family spent the summers in the mid-1950s. Later on, as a 15-year-old folkie from Boston, I was aware that there was a country dance outfit scheduled to appear at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 but I was more focused on Bob Dylan’s presence there with a blues band. I went “back to the land” at age 19 in early 1969, moving up to Northfield, New Hampshire, and started attending and playing at dances that summer. Like many other things, it was a whole new world to a city boy!

In the introduction to your book, you refer to New England country dance as a form of “creative communal expression.” Why do you think that’s important?

I’d say it’s important on two levels: first, since we live in a period of uninformed rhetoric, it actually puts us in touch with the experience that early Americans had on the eastern frontier. We pay a lot of lip service to muskets and three-cornered hats without making much of an effort to understand how interdependent people were in those days, how much their individual survival depended upon their functioning as a “united” community. We often have no real idea of what an elevated position the New England frontier had already achieved over the course of 200 years in art, in literature, in singing, and in dancing, as well as in beginning to define and defend human rights.

To the degree that our modern experience has left us divided, isolated, and even depressed, it is important for us to understand that such feelings are neither inevitable nor inescapable. Our impulses to create and share are part of our basic nature, and can be sources of joy and harmony that we overlook to our loss and our distress. The human contact involved in country dance is part of a cultural inheritance that we can draw from readily in our daily lives.

What role did your book’s subject, Dudley Laufman, play in giving this ten-thousand-year-old tradition new life?

Dudley came along at a really crucial time in the life of country dance. The form was an integral part of colonial and early American history, but it was running out of fashion by the latter part of the 1800s. Ralph Page and a group of musicians from southwestern New Hampshire were among the few who kept it alive through their appearances from the 1930s through the 1950s.

Dudley had developed a deep affection for the old ways while in high school and he took all the excitement and creativity of old-time music into his heart. What he could not have predicted was that, beginning around 1965, rural New England would be inundated by young people spilling up from the cities to find new lives in the countryside. Dudley found himself very suddenly transformed from being a young acolyte among the elders into being a sort of a pied piper of the young. Dances that had been fortunate to draw a handful were soon jammed to overflowing with couples willing to learn all the old steps and to throw their lots in with the old ways. By the mid-1970s, Dudley’s influence was spreading all across the continent, through his tireless playing at folk festivals and from the hundreds of young players and callers with whom he freely shared his knowledge and craft. Once they were promoted outside of a few dozen towns in New England, the old dances spread out and flourished in nearly all the 50 states. Dudley Laufman acted as a sort of Johnny Appleseed for antique traditions, some of which predate recorded human history.

In 2009, Laufman received major recognition for his work — the NEA’s National Heritage Fellowship Award, the nation’s highest honor in the folk and traditional arts. Can you tell us about that, and about people’s reaction to it?

During the 1960s Folk Revival, youthful musicians had been reverential of traditional artists who were in their sixties and seventies. Senior figures like Almeda Reynolds, Elizabeth Cotton, Pete Seeger, and Mississippi John Hurt were all revered after being “discovered” by young folk enthusiasts. John Hurt went from an income of a few hundred dollars a year as a cotton picker to earning a thousand dollars a night at folk and blues festivals. Given the nature of things, it seemed important to recognize these artists “officially” while they were living, and it was that impulse that led to formal acts of recognition such as the National Heritage Fellowship Award, among others. By the year 2000 the folk music revival had matured into concentration on what we now refer to as “roots music” and, if anything, the reverence for longevity deepened and increased.

In Dudley’s case, I remember the sense that his 2009 award was a celebration of the culture of New England in general and of New Hampshire in particular. I think there’s been a general recognition that we would be well-served by reviving our focus on regional culture here in New England, a sense that we could pick up our game here a bit. Perhaps that was what Ernest Thompson, author of “On Golden Pond,” was getting at when he said “I think Dudley Laufman belongs in the pantheon of genuine American artists. He belongs in Franconia Notch, the real Old Man of the Mountain.”

In any event, since the award there’s been a general recognition of both Dudley’s longevity and his accomplishments. I think there’s a logarithmic effect to seniority that sets in after about age 80, and that people have now awakened to the breadth and depth of his knowledge and experience. He is now, as far as we know, the oldest active caller on the continent. That’s pretty tall cotton, as they say in the South!

What’s the connection between country dance and the folk revival of the 1960s and 1970s?

In the 1940s, country dance was being kept alive in scattered rural communities in New England along with a few academic enclaves like Cambridge and Boston. By the mid-1950s, the Folk Revival began springing up in these same places, with additional emphasis around the UMass, Amherst, and U of Maine campuses. The two forms shared a devotion to traditional music, while the bulk of the Revival gravitated also toward the musical expression of political issues, particularly the Civil Rights movement.

The more apolitical side of the Revival was expressed in authenticity and musicianship. Although idioms differed, the emphasis on virtuosity was shared by blues players, bluegrass groups, jug bands, and country dance musicians, all of which came to be represented as minority interests at the popular folk festivals. There was an enormous increase in the number of amateur guitar players who learned their craft during the Revival; a number of these, particularly women, led the singer-songwriter movement in the 1970s and beyond. Country dance was the most widely participatory of all the forms of music in the Folk Revival, since the dancers were as much “performers” as the musicians were. And, once “folkies” began moving to rural areas, contradance became a portal into local culture and community.

What’s the state of country dance in New England today? Like, could we go do it this weekend?

Through the work of skilled pastkeepers like Dudley Laufman, the community art form of country dancing has attained a popularity probably unmatched since the Civil War. Up until about three years ago, the revival had reached the point when dances were being held in most towns and every county in New England on a weekly basis. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 outbreak that began in 2020 has restricted much of this activity, particularly during the winter months when dances are held indoors amidst the close personal contact of swings, steps, and promenades. With the introduction of vaccines, the use of masks, and general increase in understanding of the seasonality of outbreaks, the tradition has begun to regain its position on the regional calendar of events. The website ContraDanceLinks.com can point you in the right direction for this weekend and beyond!

You play music with Dudley Laufman on occasion. What’s that like, and what’s he doing these days?

Dudley is a down-to-earth Yankee: what you see is what you get. He has strong opinions, but he also has a great sense of humor. He has a keen eye for subtlety. His heart is an emotional rolodex: he has instant recall of thousands of musicians, dancers, and events, and he can tell good stories about all of them. He finds an immense amount of joy in the craft of music, and whether the subject is Cape Breton fiddling or contradancing in Tunbridge, Vermont, he takes on the role of tradition-bearer effortlessly.

There is more than a little wizardry in play in Dudley’s personality. Without fanfare or theatricals, I think he knows that traditional music is a form of magic. At his age (and this has been true for decades now) he values the promise of the moment and he curates a charismatic optimism about the future. He is as much a dairyman and a gardener as he is a musician, and his connection to the landscape is first nature to him. When circumstances require, he can move pretty effortlessly from disappointment to anticipation. In his eyes, if the apple crop is thin this year, then a big harvest is all the more likely next fall.

Playing with Dudley is a joy. He is a natural leader who can quickly size up the capacity of any group of musicians or dancers and then adjusts the course and tenor of the play accordingly. He neither suffers fools nor holds back praise. I still have the first $20 bill he ever gave me at the close of a long gig at St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire, and I can still hear him saying “You know what you’re doing.” I hope he feels that way when he reads this book, too.

Within a certain degree of restriction, at the age of 92 Dudley is doing what he always does: playing at weddings, pulling together a group of musicians to run up to a dance in Tamworth or Nelson, making the rounds at Maine Fiddle Camp, and attending all the moveable feasts that happen in and around his Canterbury home. His bird feeder and his woodpile are always full, and the coffee pot is always piping hot.

View Print Edition

View Print Edition