Dr. Eric Kropp: Changing how we view the economics of health care one patient at a time

Leading up to last year’s midterm elections, NBC News and the Wall Street Journal found health care to be the most important issue to voters. The opioid crisis, skyrocketing insurance costs, and millionaire hospital executives fill headlines. While everyone agrees that the current health care system is broken, few agree on how to fix it—and instead of solutions, we get rhetoric, outrage, and politicking.

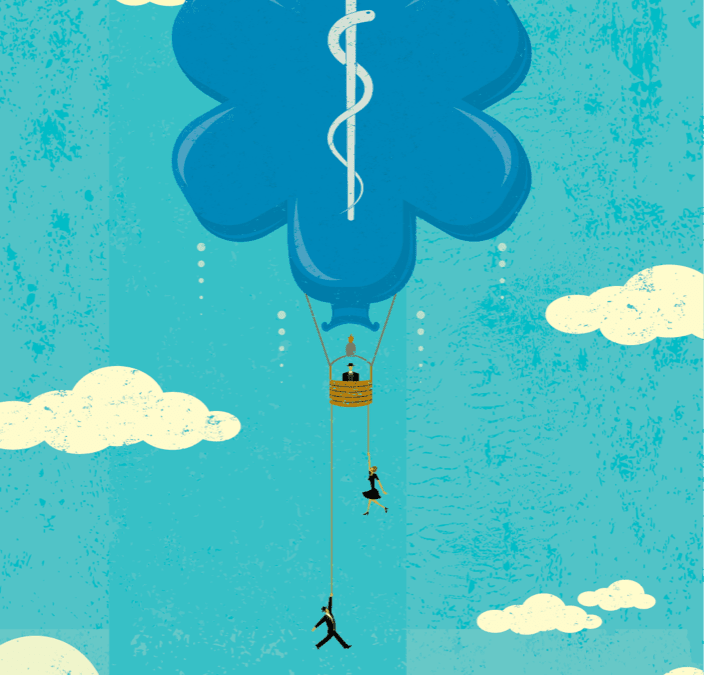

In such a climate, how will anything ever change? In such desperate times, setting the situation straight will take nothing less than freedom fighters, giant slayers, and boatloads of courage. In other words, people like Dr. Eric Kropp.

Probably never one to consider himself a freedom fighter or giant slayer—and probably the first to admit that some of his life decisions have been scary—Dr. Kropp is a family physician. His practice, Active Choice Healthcare in Concord, uses a model known as DPC, or direct primary care. In DPC, patients pay an affordable monthly fee that includes routine and preventative visits, checkups, and urgent and chronic care.

According to Dr. Kropp, when primary care operates the way it should, it can address 90 percent of a patient’s needs. No third parties, no premiums, no deductibles. Sound revolutionary? “Really, it’s trying to make it about patients and their doctors—nobody else,” Dr. Kropp says.

A Physician’s Experience

Dr. Kropp’s interest in medicine began as a teen. “I loved studying the sciences,” he says. With his love of science, he developed a fantasy of a country doctor like in the old days. Back then, doctors knew their patients, they were accessible when needed, and they took time to get to the bottom of patients’ ailments.

He attended medical school at St. Matthews University in Grand Cayman and completed a New Hampshire Dartmouth Family Medicine residency before practicing in a traditional family health care clinic for six years. As he cared for and treated patients—and managed the overflow of related paperwork—he came to a startling realization. “Did you know,” he asks, “that as much as 30 to 40 percent of a physician’s day is spent on administrative duties?” He adds, “I spent all that time interacting with a computer and not with patients.”

These duties, among other things, include documenting and justifying treatments and interventions for third-party payers (i.e., public and private insurers). It was a far cry from the country doctor daydream of his youth.

Meanwhile, despite the paperwork, a physician’s patient load doesn’t get smaller. If anything, physicians working in traditional insurance-based practices must see more and more patients. Have you ever looked at your medical bill and noticed that your insurance company pays only a fraction of what your provider charges for a service? Well, that is correct. Insurance companies dictate to medical practices what they pay for services, not the other way around.

Meanwhile, have you ever wondered why you sit in a waiting room for an hour only to see your doctor for five or six minutes? “Many doctors have 1,500 patients,” says Dr. Kropp. During his time in the traditional practice, he would see patients, then enter into hours of paperwork. “I’d get home at 8pm,” he says. “It began to take away from my ability to care for myself and my family.”

Dr. Kropp says the morale among physicians is low, and it’s not hard to imagine why. “For me, it wasn’t burnout,” he says. “It was moral injury.” He simply didn’t feel good about the care he was providing as a result of the system around him. And he didn’t feel good about his own self-care. Something had to give.

Making It Right

Fast-forward to the present day. Chuck Cosseboom of Deerfield recently had an infection in his foot. “I texted Dr. Kropp at 7:15am,” Chuck says. Dr. Kropp—not a secretary or office worker (Dr. Kropp only has two employees; one is an RN and the other is his wife)—responded at 7:20 telling him to come to the office at 9am. “At 9:15, he had seen me, and I was walking out with the antibiotics to fix the infection,” Chuck says.

Wait, you say. Chuck is texting with his doctor? He didn’t sit in the waiting room? And he was out in 15 minutes?

Dr. Kropp has 500 patients. His wife manages his practice, which opened in 2016. If you call, you’ll get one of them. Dr. Kropp doesn’t employ a whole office staff because he doesn’t need a staff to deal with paperwork associated with insurance. “Direct primary care is the alternative to the fee-for-services model,” he says. “The patient pays a flat fee and you’re free from third-party involvement.”

Like a cell phone with its a monthly bill rather than paying by the call, DPC patients pay the same amount each month regardless of the number of visits. “I see some patients once a year; I see some once a month,” Dr. Kropp says. He adds that his familiarity with patients often allows him to pass on low-yield, high-cost tests that a more traditional clinic would likely order. He also does as much of his own lab work as possible, often at a lesser cost to patients.

The decision to open one’s own practice would be big on its own. But to open an insurance-free practice in an insurance-obsessed country? “It was scary,” Dr. Kropp admits, noting that the DPC model was not covered at medical school. This means that any doctor seeking to open a practice on the DPC model would have to learn to fly without many resources available to help guide them. When one considers the amount of medical school debt doctors take on . . . scary, indeed. And Dr. Kropp, who doesn’t have a business degree, does have a wife and three kids.

When he opened his practice, there were even fewer resources available to doctors about the DPC model than there are today, despite the fact that DPC numbers were and are growing. In fact, a few years ago at a conference for regional health care providers, a number of New England physicians in attendance who were interested in learning more about DPC held their own informal “un-conference” to share what they knew about DPC. The meeting spawned the New England Direct Primary Care Alliance (NEDPCA). The revolution had begun.

A Slow Tsunami

As far as revolutions go, this one is pretty snail-like. After all, we’re talking about changing the culture of health care one physician and one patient at a time. “It’s a slow tsunami,” says Jeffrey Gold, MD, of Marblehead, Massachusetts, another DPC physician who attended the original un-conference and became—along with Dr. Kropp—a founder of the NEDPCA. Nationwide, the number of DPC practices have gone from 500 to 1,000 in two years.

Twenty-five states have passed legislation defining and legitimizing DPC practices. There is currently a similar bill in committee in the New Hampshire legislature. The legislation—titled HB 508—declares that primary care doctors providing direct primary care under a primary care agreement (DPC models) are not subjected to insurance laws in the state. Basically, this codifies DPC models and eases their availability to patients as long as they meet certain criteria. As of press time, the bill passed the House and Senate and is under consideration by Governor Chris Sununu.

“I would just like for the DPC model to be a well-understood model,” says Dr. Kropp, who also sees DPC as a positive alternative for businesses that provide health care benefits.

However, in an insurance-dominated system, many people get frightened off by a practice that doesn’t work with insurance. “DPC can coexist with insurance,” he explains. You wouldn’t use your auto insurance to pay for an oil change. Rather, you use insurance when your car gets totaled. Dr. Kropp suggests DPC combined with a larger deductible (and therefore less-expensive) policy for catastrophic injury or illness could make for a good mix.

“I’m not competing with insurance,” he says. Also, he points out preventative care is an investment against more expensive treatment for a preventable illness. “For every dollar you invest in primary care,” he says, “you save $15 later.”

“I’d like to work with insurers,” says Dr. Gold. “Not for them.”

A revolution is happening at a small, single-doctor practice in Concord, New Hampshire, and at similar practices across the country. History is being made, and giants are being challenged.

“How do we get people to realize that change doesn’t happen at the top?” Dr. Kropp asks. Change starts at the bottom, he says, where people who are just as important as those at the top make one decision at a time to do the right thing.

“We’re trying to make health care about the patients, not the rule makers,” says Dr. Gold. And in the end, when you make that 3am phone call to your primary, who’s going to take care of you—your senator? The CEO of an insurance company? “Of course not,” says Dr. Gold. Your doctor is.

View Print Edition

View Print Edition

FYI, a minor correction — HB 508 is in a conference committee as of the time of this publication.

Direct Primary Care is something we need a lot more of in this country to get better quality care at lower costs. I’m glad that we have Dr. Kropp in New Hampshire and wish we had more DPC providers.